Establishing our Parks & Preserves

John Brooks Park Beachside and the Jane Murray Brooks Park on South Hutchinson Island

The CASLC came into being in 1972 to seize a rare opportunity to preserve pristine land bordering the Atlantic Ocean and Fort Pierce Inlet.

We rallied local residents and civic organizations to petition the state of Florida to establish the Fort Pierce Inlet State Park. Our success met with gratitude from residents who felt assured that this special area would be protected for generations to come. In 1977 we celebrated our second big success: the Alliance, and noted environmentalists from Martin County, Maggy Hurchalla and Dr. Richard Stokes, lobbied for the creation of the Savannas Preserve State Park. It is now the largest contiguous freshwater marshland along the southeast coast, and provides key ecological services to the Indian River Lagoon and habitats for hundreds of native species.

In the 1980s we worked to establish the Indian River Lagoon Aquatic Preserve, and staff it with its first manager in Fort Pierce. Today. the entire multi-county 156-mile long Indian River Lagoon is considered to be the most biodiverse estuary in North America, and has been established as a National Estuary, with 5 state parks, 4 federal wildlife refuges, and a national seashore. It also includes portions of the North Fork of the St. Lucie River in St. Lucie County. The first and second Riverkeepers arose from our Board.

By 1989, our first effort to assure passage of a $10 million bond to purchase six St. Lucie County beaches was successful. Two parks that protect nearly 400 acres were named after our founders: John Brooks Park Beachside and the Jane Murray Brooks Park on South Hutchinson Island.

Our Land 4U2 Campaign resulted in passage of a $20 million bond to buy environmentally sensitive land in St. Lucie County.

In 2011 we advocated for the establishment of the Mariposa Cane Slough Preserve in Port St. Lucie, which we adopted.

All told, the Alliance is either directly or indirectly responsible for the conservation and protected status of thousands of acres of land and water in St. Lucie County in state, county, and city nature preserves.

Defending our Parks & Preserves

Hiking Trail Marker: Photo by Paul Strauss

Our Founders understood the urgent need to set aside for conservation the most pristine and ecologically important areas due to what was already evident in Florida in the 1970s: rapid population growth and development. They could not have foreseen, however, the nearly exponential increase in the number of new residents and the ever-growing expansion of development consuming and altering our lands and waters.

What was also difficult to foresee was the threat to the very mission of our state parks and to any other declared conserved or preserved areas: to protect their special land and waterscapes, integral ecologies and species habitats. We have since found that we must continue to monitor and, in some cases, go to bat once again to protect areas that were already considered safely housed within a park, preserve, conservation easement, or designated protected areas.

Savannas Preserve bobcat amidst bachelor buttons: Photo by Paul J. Milette

Crosstown Parkway Bridge: Lessons Learned and Shared

Savannas Preserve Beauty Berry: Photo by Paul J. Milette

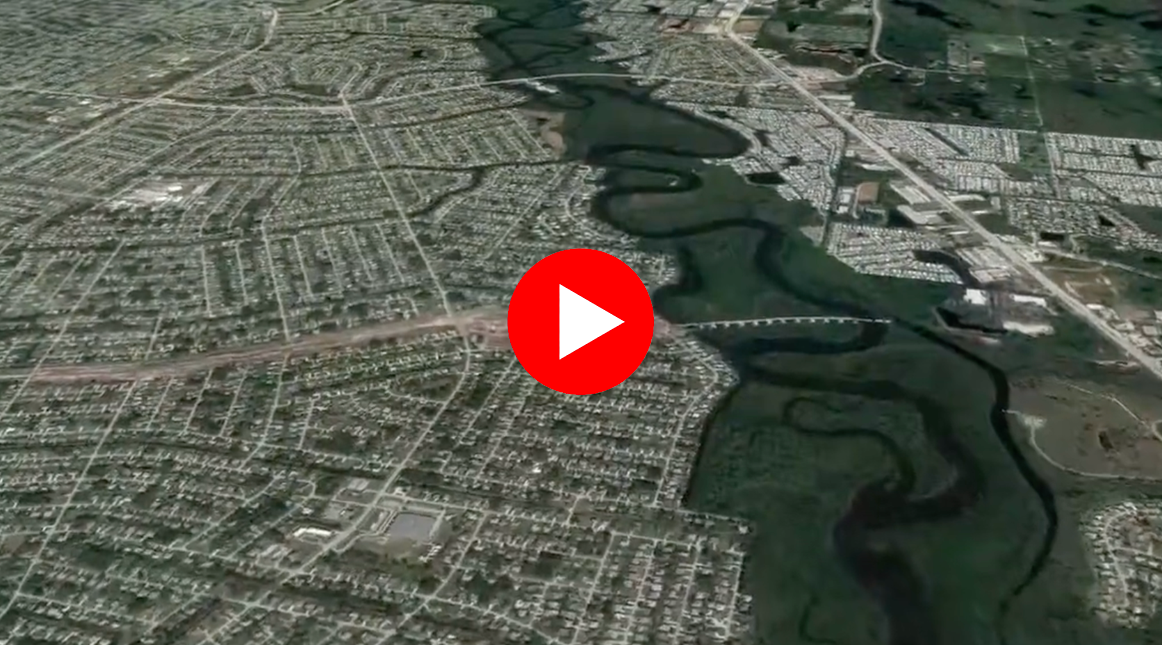

The Alliance fought for nearly two decades to stop the Crosstown Parkway in Port St. Lucie from being built through the Savannas Preserve State Park (SPSP) marshland and the Indian River Lagoon Aquatic Preserve, the Halpatiokee Buffer State Preserve, (now managed by SPSP) and the North Fork of the St. Lucie River Aquatic Preserve. Notice the number of times “Preserve” is in the name of these parklands.

The controversy of using our Preserve State Parklands and our State Aquatic Preserves for the city of Port St. Lucie’s Crosstown Parkway (CTP) began heating up in the mid-1990s. The City envisioned a parkway extending from I95 all the way east to the Narrows section of South Hutchinson Island. CASLC coordinated with citizens, civic and environmental groups, and attorneys, with the result that the proposed eastern most leg of the CTP through the SPSP marshlands and the Indian River Lagoon Aquatic Preserve was defeated in 2000.

The city’s next strategy was to begin the Parkway from the west and work east. Both CASLC and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection called for an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to be performed for the entire proposed route—from I-95 east to Hutchinson Island on the Atlantic Ocean. This comprehensive EIS would have more accurately reflected parkland and ecological consequences of the CTP. It was never done.

Rather, it was agreed that the CTP project would be “de-federalized” in order to segment the different phases and thus achieve easier approval from the regulatory agencies. The political commitment to the conservation mission of our state parks began to waiver.

The biggest and last hurdle for the CTP to reach US1 was to devise the means by which the Halpatiokee Buffer State Preserve could be appropriated for a bridge nearly ¾ of a mile long over the North Fork of the St. Lucie River Aquatic Preserve. Because this area protected the largest, most contiguous and pristine historic floodplains and wetlands along the North Fork, a tributary of the St. Lucie River was designated as a “buffer” preserve to perpetually insure the cleanest water quality for the River.

As early as 1990 the proposal to use the Halpatiokee area for a bridge was uniformly denounced by all federal, state, and local agencies: the CTP bridge route was the worse route due to the extent of wetland destruction and ecological degradation it would cause. The agencies insisted the city choose one of the other six alternative routes which were far less damaging to floodplains, wetlands and species habitats, as well as options that would take no state parklands. Dividing such preserves in half would set a terrible precedent.

In the end those strong objections did not matter. After many years of political maneuvering the “powers that be” agreed that our “ecological gem” could be negotiated away.

In 2017 we lost the legal battle with the Federal Highway Administration and the U.S. Department of Transportation in the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. Our co-plaintiff, the Indian Riverkeeper, fought valiantly alongside us. The Alliance provided two expert witnesses for the State Administrative Hearing that Audubon of St. Lucie County initiated in another unsuccessful effort to protect Halpatiokee.

It was a noble fight. We made videos, held protests, got lots of media coverage, wrote op-eds, created online petitions, sought support from numerous environmental organizations, a noted local ichthyologist, master naturalists, and ecologists. We filed lawsuits, and scoured through tens of thousands of pages of documents for our attorneys and wrote summary reports.

“A first ever taking of a Preserve State Park for highway infrastructure. Essentially bifurcating the intact buffer ecosystem, and setting precedent.”

George Jones, former CASLC President, retired Bureau Chief for District 5 of Florida State Parks. Photo by Paul J. Milette

Labor of Love

Our fight was been a labor of love. The Halpatiokee Buffer Preserve was a place of natural beauty, an awe-inspiring “ecological gem” that hosted an unexpected diversity of habitats and species, a few of which are, or were, very rare. It inspired a deep emotional bond in us. We hope that in sharing our story we can prevent this tragedy befalling another state preserve.

It is an ongoing challenge to monitor legislation being proposed that affects our parks and our quality of life in Florida. For example, in 2020 along with 120 organizations CASLC signed on to Sierra Club’s letter to FDOT challenging M-CORES. The proposed 330 miles of toll roads would cut through environmentally sensitive lands, including state parks and preserves, and affect water quality.

It matters who we elect to state offices: in the wrong political climate, no state park is protected, even those qualifying as a “Preserve.”

Air Plant

Savannas Preserve State Park

White Water Lily: Photo by Paul Strauss

In 2017 CASLC became aware that new politics were seeking to redefine how our state parks could be used, indeed, their very mission. CASLC joined with the grassroots organization “Florida State Parks in Peril” to defend the approved use of the Savannas as a Preserve against “incompatible uses,” like cattle grazing, that were proposed. We were successful.

In 2024 yet another effort was made to convert our award-winning state parks (including the Savannas) to incompatible uses such as golf courses, hotels and other habitat destructive uses. Local citizens, including CASLC members, made their voices heard and the state-wide proposals were scrapped. For now. Continued monitoring of political forces is essential.

An additional calculation that should be made in the future is to assign monetary value to the ecosystem services that SPSP provides. For example, as a large marshland area SPSP readily provides water storage and cleansing services as well as increasingly rare habitats for our native Florida flora and fauna.

Above and below, Flatwoods Savannas Preserve. Photos by Paul J. Milette

A Trail by the River

A blog by John Bradford

Lying just west of US intersected by Village Green Drive was the awe-inspiring Halpatiokee Buffer Preserve owned by the Savannas Preserve State Park. Here one found the Halpatiokee Nature Trails which meandered through several diverse terrestrial and riverine ecosystems, ending at Evans Creek, a tributary of the North Fork of the St. Lucie River.

Take a look at the pictures of the flora and fauna that were found here … and understand why we fought so hard to save this special place.

John Bradford is an avid naturalist and plant photographer. His email address is cyclura@bellsouth.net

In 2019, Dr. Gary Goforth, a veteran scientist who has been studying and restoring local waterways for more than 35 years, gave a presentation on the State of the North Fork of the St. Lucie River. The North Fork was designated a Florida Aquatic Preserve in 1972 with the goal of protecting its “aesthetic, biological, and scientific values.” It’s also part of Everglades Restoration and the “Save Our Rivers” Program.

Oculina Deep Water Coral Habitat Area of Particular Concern

In the 1970s, scientists from what is now known as Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Institute (HBOI) in Fort Pierce, discovered a unique-in-the world deep water Oculina Coral Reef Bank that exists between 15 and 45 miles off of Florida’s eastern coast.

Led by senior scientist, Professor John Reed (now retired), HBOI conducted voluminous research that established both the critical import of this coral reef ecosystem but also that 90% of it had already been destroyed by the Florida east coast bottom trawling rock shrimpers.

In 1984, Professor Reed (now a CASLC board member) and fellow scientists made a successful case to the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council (SAFMC) for a protective designation of “Habitat Area of Particular Concern (HAPC),” which would make it illegal to trawl, use fish traps, long lines or anchor. This is a national designation and considered to be part of the Marine Protected Areas Act.

Photo courtesy John Reed, Harbor Branch

The science is clear. The economics are clear. The ethical and moral mandates are clear. What remains of the intact Florida Oculina reef system and the associated damaged areas, if left alone—and protected from fishing, especially trawling, will yield enduring benefits now and forever. Giving a few shrimpers a green light to trawl these ancient systems into oblivion will destroy what could be an ongoing source of life and livelihoods in exchange for a few bucks for a few people and then it will be over.

Sylvia Earle, former chief scientist for NOAA, head of Mission Blue and Explorer-in-Residence for National Geographic.

Photo courtesy of John Reed, Harbor Branch

As the fragile, very slow-growing coral began recovering, the value of this ecosystem became clearer as research continued. Oculina Corals are thousands of years old, and serve as a keystone species providing incredible marine and estuarine productivity (with fish interconnectivity to the Indian River Lagoon).

A single 12-inch coral can host up to 2,000 animals. A branching coral can grow up to 10 to 20 meters in height. The ecosystem serves as a migration pathway, spawning and nursery grounds, mating opportunities, shelter, and hosts numerous and varied fishes, some of which are recreationally important, and some of which are threatened and depend on this habitat in particular. It has been established that the coral reef bank extends all the way up to St. Augustine.

In 2020, the SAFMC sought to allow a handful of rock shrimp trawlers off of Florida’s central eastern coast to move into Oculina’s HAPC proximate borders due to the passage of Amendment 10, a Trump Administration’s Executive Order, which gave a green light to industries wishing to make use of previously established protected conservation areas.

CASLC kicked into high gear. We created an online petition and submitted public comments to the SAFMC. After SAFMC approved the request by the rock shrimpers we initiated a national campaign. We partnered with the Marine Conservation Institute (MCI) in Washington, DC. The next step was to contest the SAFMC’s ruling to the final decision maker: the National Organization for Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA).

We galvanized local and state environmental organizations to champion Oculina’s cause and to sign on to the CASLC’s comments to NOAA. MCI created another online petition that generated over 40,000 signatures. A cadre of nationally reputable scientists, including local Dr. Edie Widder of ORCA and ichthyologist, Dr. Grant Gilmore, submitted their substantive, research-based comments. Famed oceanographer, Dr. Sylvia Earle, chimed in as well.

Our persistent efforts paid off: NOAA turned down the rock shrimpers request to trawl in immediate proximity to Oculina Reef. However, NOAA left the door partially open for future requests to reconsider its decision. Hence the need to monitor any move to open up the HAPC by the rock shrimpers. We favor development of methods ensuring that unseen violations be documented and the HAPC’s constraints be enforced.

No fish habitat, no fish.

Grant Gilmore, Ph.D. ichthyologist, Estuarine, Coastal & Ocean Science

Florida PBS Changing Seas Episode 103: Corals of the Deep. In the deep waters off Florida’s Atlantic coast grow magnificent structures, capable of reaching 300 feet in height. These are the corals of the deep sea. Porcelain-white and centuries old, few humans have seen these delicate reefs. The ivory tree coral, Oculina varicosa, and Lophelia pertusa flourish in harsh, sunless environments, yet these branch-like formations provide food and shelter for a variety of deepwater organisms. Rich in biodiversity, this mysterious underwater kingdom is threatened by destructive fishing practices such as bottom trawling. However, a recently proposed 23,000 square mile marine protected area could save these fragile reefs from ruin. Click to view.

Oculina Reef: Photo by John Reed

Halpatiokee Archive

Lawsuit, Petition, Public Comment Documents

- CASLC Letter to the Coast Guard

- Lawsuit to Move Bridge Location

- Petition to Stop Test Bores

- Legal Brief filed by the Conservation Alliance and the Indian Riverkeeper

- Conservation Alliance and Riverkeeper Appeals Court Brief

- Public comment—Shari Anker, President of the Conservation Alliance

- Public comment—Beverly Yoshioka

- Appeals Brief

- North Fork St. Lucie River Floodplain Vegetation Technical Report” (WR-2015-005)

- Letter to Greg Oravec, mayor of Port St. Lucie, from Anne Cox, president of the Florida Native Plant Society

- “Biological investigation and review” by ecologist Greg Braun, for the DOAH hearings re: easement and Environmental Resource Permit issued by So. Florida Water Management District

Evans Creek Video – Creator Unknown

Save the Halpatiokee Trails video

10 PARKS THAT CHANGED AMERICA

PBS video about parks in America that includes a section on the landmark Supreme Court Overton Park decision that said no to building through parks when other alternatives are available. Open the video and scroll to about 31 seconds to see the Overton Park story and why it related to our case.