Pollution in Paradise

Florida’s natural beauty has been an exotic magnet for explorers, writers, and artists since the 19th century. Its varied waters from wetlands, marshes, streams, lakes, rivers, fresh water springs, estuaries and lagoons to the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico enabled a highly biodiverse flora and fauna to evolve from this ubiquitous and abundant resource.

These waters are created from the geohydrological cycles of a peninsular state surrounded by water on three sides. Every other land mass around the world at this latitude is a desert. The movement of warm waters off our coast moderates our climate and produces abundant life-giving rain. Complemented with also-abundant days of sunshine, Florida’s species took every advantage and turned Florida into a “Paradise.”

Florida’s paradise initially attracted only a very slow trickle of new (often hearty) residents, lured by Florida’s natural beauty, outdoor activities like fishing, and relaxed lifestyle through the mid-20th century.

About this time Everglades champion Marjory Stoneman Douglas warned that with the invention of the air-conditioner Florida would forever be changed. A stampede of people now made comfortable in artificially cooled buildings would cause heretofore unknown stresses to Florida’s delicate ecological balance. Hardest and most immediately hit was Florida’s pristine waters. Other issues arose like air pollution as well.

Florida today is the third most populous state in the nation, and people are still coming. The need for environmental activism in every part of the state, in every ecosystem, can be overwhelming because the impact is so great. For sustenance and inspiration we can learn from our own hometown writer, Ernest F. Lyons.

Ernest F. Lyons

Ernie Lyons & the St. Lucie River

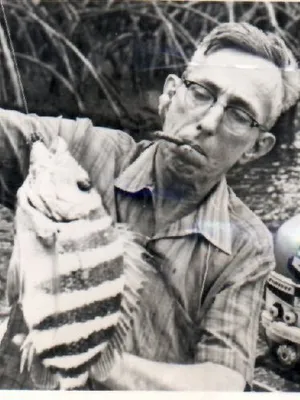

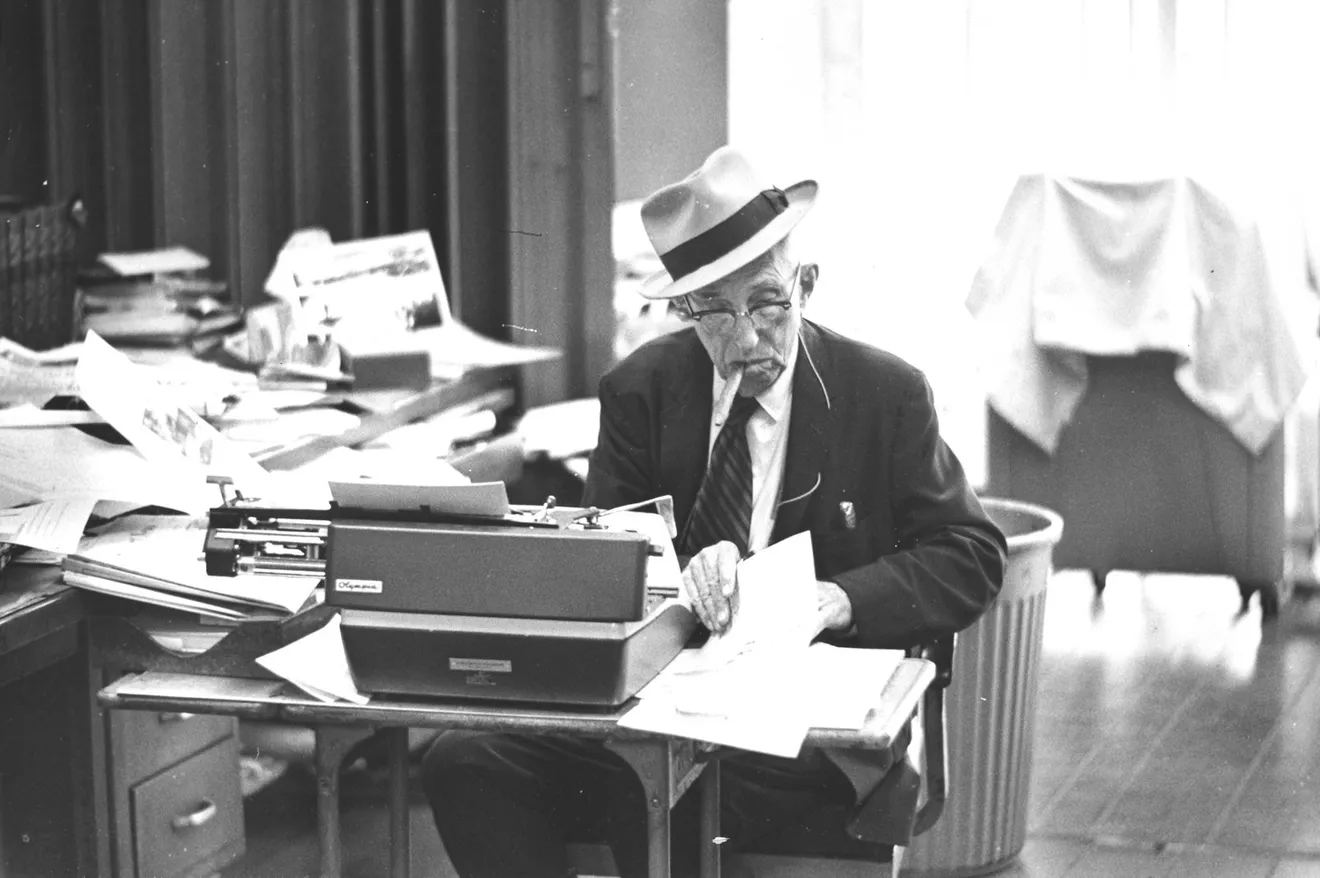

On the Treasure Coast, our very own version of a barefooted Huckleberry Finn, “Ernie” Lyons, at age 13 in 1915, began a life-long love affair with the St. Lucie River, which he called his closest friend. Later, as editor of The News, his weekly columns documented his joyful boyhood expeditions on the St. Lucie River, along the South Fork in Martin County, and the North Fork in St. Lucie County. His writing style has been compared to that of Mark Twain, and he received numerous state and national awards for conservation writing.

“Rio de Luz” was Ernie’s favorite name for the River. It came from the first Spanish explorers who marveled at its luminescence at dawn, a “river of light.” Ernie experienced “fish-filled mystic pools and game laden woods.” The Headwaters of both Forks were fed by networks of marshlands and tributaries which, after rains, continually refreshed the river with clean and drinkable water. Expansive floodplains and forested wetlands stored and cleansed the water.

When Ernie arrived, the lower reaches of the River had just been connected to the Atlantic Ocean via an opened St. Lucie Inlet, which also connected to the Indian River Lagoon, creating an estuarine water zone at the new mouth of the River. The St. Lucie was heralded as the most biodiverse body of water in North America.

Ernie’s writings reflected not only on the natural majesty of the River, but also on the River’s step-wise degradations at the hands of humans over time as population, development and industry moved in. Our abundant waters became a problem to be solved under humanity’s control: re-plumb, re-direct, and dry out. Our waters also became a convenient receptacle for our wastes. What Ernie documented was and is happening all over the state, and we have much to learn from him.

In Ernie’s Words: Those Were the Days

I often think of the St. Lucie as a giant sprawled on his back in the grass, with his feet in the sea, his right arms extended lazily up the reaches of the South Fork, his left up the North Fork. The grass is the forests of virgin pines, the cabbage palm hammocks and mangrove swamps which outline his body when I first knew him as a boy. … For many years, into my young manhood, this recumbent giant of a river was my closest friend.

From “The Gifts of the Wonderful River”, October 2, 1958, transcribed by Sandra Thurlow on July 18, 2011

Cabbage Palm: Photo by Paul Strauss

The river fed us. You could get all the big fat mullet you wanted with a cast net or spear. If you were really lazy, you could leave a lantern burning in a tethered rowboat overnight, and half a dozen mullet would jump in, ready to be picked up on the boat bottom next morning. Going up or downstream by boat, you would scare the ‘golden plate’ pompano which would come skipping over the water like tossed dinner plates, apt as not to land in the boat.

The river for me was a way of escape. Always it was there beckoning, with its palm-bordered bands unfolding like the scenery on a stage … alligators sliding from every bend, not one or two but a dozen or so … manatees rising and sighing … the great silver tarpon leaping in the air as they charged into schools of mullet. Every free moment, I haunted the river.

St. Lucie River: Photo by Paul Strauss

There was never anything more beautiful than a natural South Florida River, like the North and South Forks of the St. Lucie …. Their banks of cabbage palms and live oaks draped with Spanish moss and studded with crimson flowered air plants and delicate wild orchids were scenes of tropical wonder, reflected back from the mirror-like onyx surface of the water….

Jacqui Thurlow’s blog, “Ten and Five Mile Creeks, the Once Glorious Headwaters of the North Fork of the St. Lucie River”, May 6, 2004

In Ernie’s Words: Humanity’s Folly and the River’s Headwaters

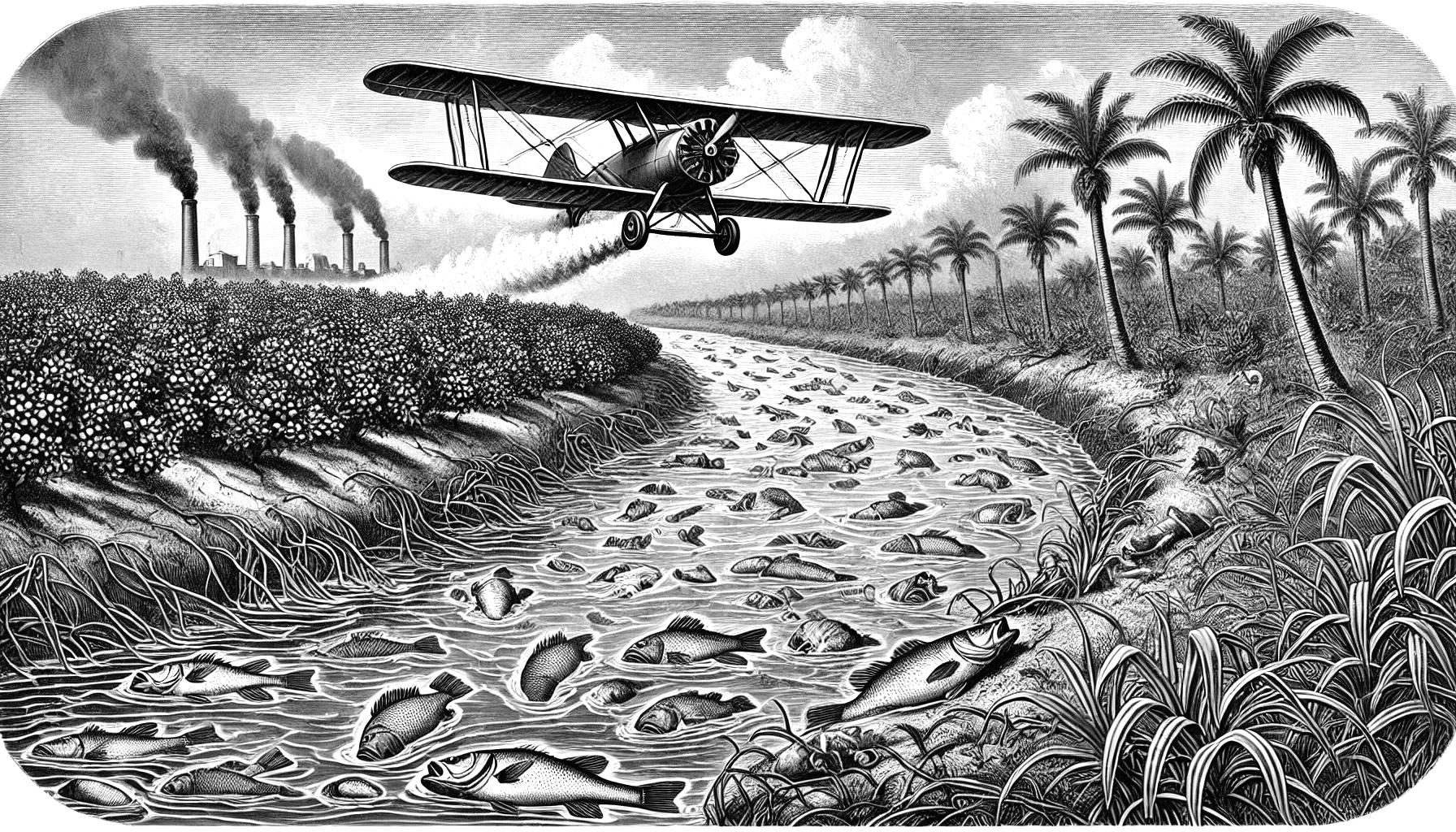

Vast citrus plantings were put in upstream…. They were sprayed by airplanes with powerful insecticides …. When the good rains came the other day, they were good no longer, but very bad.

The Headwaters of the River, once an asset to Florida and the nation, reeked with dead fish, killed by pesticides from run-off from drainage from orange groves. Biologists counted thousands of dead black bass, blue gills and catfish floating on the surface, and said that many more fish would die as the poisonous water drifted downstream.

We turned our good, sweet water into a cup of poison and changed a laughing little river into a reeking abomination—in the latter part of an ordinary lifetime.

From: “Clean Streams are not Forever Like a Sunrise,” in The Last Cracker Barrell, Newspaper Enterprise Association, January 1, 1975

Drainage canals mostly for agricultural purposes, cut the throats of the upper rivers. During periods of heavy rainfall, muddy waters gushed down and turned the formerly clear streams into a turbid, silted mess. During dry spells, gated dams held back the water for irrigation. The water table was lowered. Salt marched upstream, turning the formerly fresh waters brackish and eventually so salty that fresh water fish could not procreate.

Jacqui Thurlow’s blog, “Ten and Five Mile Creeks, the Once Glorious Headwaters of the North Fork of the St. Lucie River”.

In Ernie’s Words: Inspiration to Action

THE RIVER which has always changed and is always changing, which was fresh water with lilypads and manatee grass and big black bass most of the way downstream until early settlers reopened St. Lucie Inlet, and it will continue to be only if we can clean it up and keep it clean.

WATER IS ONLY WATER but water can be wonderful, a happy part of happy lives, only if you don’t mix mud and pesticides and chemicals and blue-green algae with it—after which it becomes a problem and the river’s mood becomes despair.

WHAT MEN DO they can undo, and the hope for our river is in the hundreds of men and women in our communities who are resolved to save the St. Lucie. It may be too soon for the river to have a mood of confidence but it is not too soon to hope.

From “Moods of River Always Changing for Better or Worse,” December 3, 1970, transcribed by Sandra Thurlow

CASLC Gets to Work: Addressing Pollution in Its Myriad Forms

- In the 1970s, we lobbied for increased safety requirements at the new Hutchinson Island nuclear power plant, such as the storm surge barrier, and stopping the warm water discharges directly into the Indian River Lagoon.

- In the 1980s our “St. Lucie River Preservation Committee” documented the pollutants coming from the citrus processing plants, resulting in major reductions of chemicals released into the North Fork.

- In 2010 CASLC won a joint lawsuit with the Indian Riverkeeper against Allied Chemical, which was injecting industrial water into a Fort Pierce aquifer located near a drinking water source. In 2013, 2020, and 2021, we lobbied against polluting industries, like cargo at the Port of Fort Pierce.

- In 2015, we lobbied against USA Compost Facility in Port St. Lucie. Their product would be highly nutrient laden biosolids, made from sewage sludge waste. As a ”fertilizer” product its nutrient levels would be highly damaging to any water body it flowed into.

- In 2017 and 2019 we lobbied against Sun Break Farms in Fort Pierce, who wished to manufacture biosolids as well.

- In 2019, Port St. Lucie agreed to stop spraying glyphosate in Mariposa Cane Slough Preserve.

Joining with Allies

CASLC Kayak Trip White City North Fork of the St. Lucie River. Marine scientists Paul and Beverly Yoshioka survey the water. Photo by John Reed

Live Oak: Photo by Paul Strauss

- In 2005 CASLC, along with Audubon, the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, (and passionate activist Dottie Hull), combined efforts to protest against a proposed coal plant in Port St. Lucie, which would have been the 6th largest in the nation at the time. An all-night meeting with the county commission with over 500+ attendees, culminated in success.

- The first two Indian Riverkeepers emerged from CASLC’s Board of Directors. We worked together on two lawsuits, the first to prevent pollution from entering our water (Allied Chemical); and the second to retain critical floodplains and wetlands along Evans Creek, a tributary of the North Fork (Halpatiokee Buffer Preserve State Park).

- We joined the potent Rivers Coalition when it was formed in the 1990s for its grassroots efforts to stop the Lake Okeechobee discharges into the St. Lucie River and Inlet, the Indian River Lagoon, and the proximate Atlantic Ocean. Contaminated with agricultural nutrient and chemical run-off the discharges catalyzed the growth of cyanobacteria (aka blue-green algae) which in some years was inches thick. Its destructive impacts cannot be overstated on our aquatic ecosystems, habitats, and species, including in the North Fork. Our fishing and tourist industries experienced steep declines, while at the same time serious human illness was documented; even pets got sick and died. Dr. Edie Widder of Ocean Research Conservation Association speaks on the harmful human impact in this short video, “The Dangers of Toxic Blue-Green Algae.” The scientific name is cyanobacteria.

- Witnessing the degradation of the most biodiverse estuary in the U.S. and Caribbean (featuring over 800 species of fish alone) devastated the local community. The Rivers Coalition became a tour de force in pushing for changes in discharge policies at the federal (US Army Corps of Engineers) and state levels (South Florida Water Management District) as well as pushing for restoration of Lake Okeechobee’s flow South, which was its historic direction (and not into the St. Lucie River and Inlet). In 2019 we submitted a letter to the US Army Corps of Engineers re: LOSOM, asking for more responsive and responsible decisions in how and when they discharge into our waterways.

Education

- In 2018 we held a screening of the documentary film, “A Plastic Ocean” at Indian River State College to promote awareness of this new and pervasive source of pollution.

In 2019 we co-hosted with St. Lucie County’s Environmental Resource Department, Gary Goforth, P.E., Ph.D., environmental engineer and water resources manager. His presentation, “For the Love of Florida: The North Fork of the St. Lucie River” was delivered to a packed county commission chambers. Here’s the link to his PowerPoint presentation, which provides a comprehensive scientific look at the North Fork, including historical watershed and flood plain maps, changes to vegetation, charts of pollutants, recent structural improvements and recommendations. Highly recommended.

- In 2020 Joanie Regan, Stormwater Manager for Cocoa Beach, presented on the forward-looking policies of “Low Impact Development” and strategies to “Restore Rain’s Natural Path.”

- In 2021 an emerging source of pollution, EMFs from wireless technology and its documented effects on flora and fauna, was presented by Theodora Scorato of Environmental Health Trust.

- In 2022 and 2023 we hosted presenters from the Florida Rights of Nature Network in order to introduce this new and international concept in protecting nature to our members. This group seeks to place those rights in ballot initiatives in order to add them to Florida’s Constitution; the most recent initiative was called The Right to Clean Water.

What's Next?

We have extensively changed our bioregion’s geohydrological cycles. Both the quantity and quality of our water is drastically different than it was during Ernie’s time.

For example, the quantity of water flowing into the North Fork has increased four times its original rate. Because we have paved over so much of our lands water that used to be absorbed, stored, and filtered now speeds its way into our canals and then into our waterways. “Peak flows” during storms produce even greater pulsed volumes of water that must be dealt with by our ecosystems, and human infrastructure.

The quality of water has been substantially impacted by a number of sources, including run-off from our roads and lawns, waste and storm water discharges, agricultural fertilizer (aka nutrient) and chemical run-off, and seepage from septic tanks.

Now that the harmful consequences of those earlier decisions are apparent, we must all, at every level, get to work.

CASLC will continue to be on the job to educate, advocate, and lobby our elected representatives to protect our waters for the lives that depend on them, human and non-human.

“Fixing the water” is complicated, however, here are some steps we can take to make a difference. We are fortunate that numerous organizations in our area have responded to our waters’ cries of distress, meaning we can join forces and make a bigger difference sooner. We provide links here and also on our Greenlinks page.

- Learn about our Indian River Lagoon’s watershed, the water’s original flow, including its floodplains and wetlands, and how it’s been altered over time. The St. Lucie County Water Champions program has videos and courses for the basics.

- Consult Dr. Goforth’s Powerpoint Presentation for big picture definition of the problem, and both nature-based and engineered solutions, like STAs or storm water treatment areas.

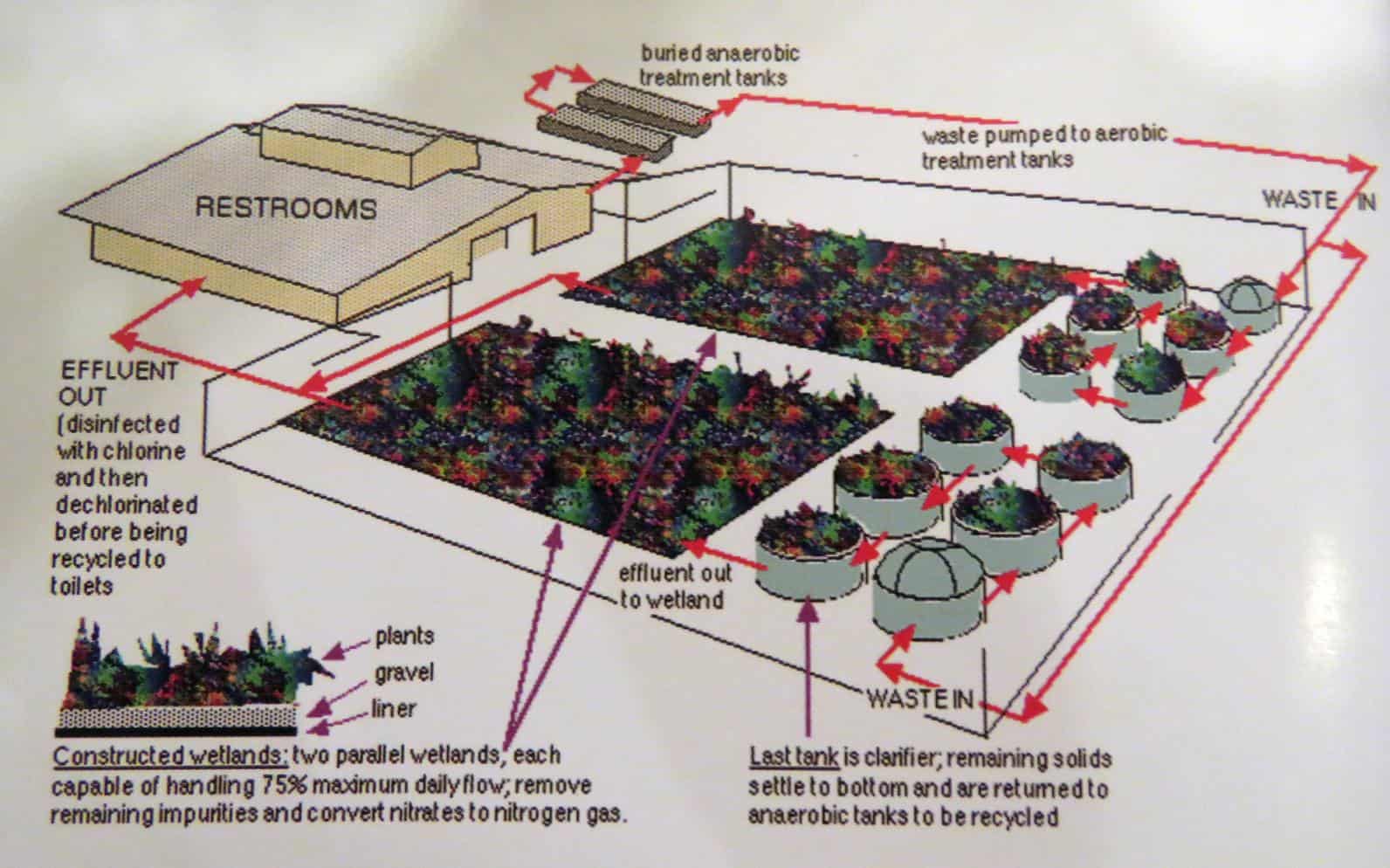

- Retain existing floodplains and wetlands. Seek to place them under protective conservation status whenever possible. Understand that Florida’s loss of wetlands is immense. Artificially created wetlands cannot readily provide the ecosystem services that the original wetlands did.

- Restore degraded or damaged aquatic ecosystems.

- Use Biomimcry to Replicate Nature’s Solutions. This powerful concept introduced by Janine Benyus in the 1990s has been widely adopted, and is very relevant to us as we attempt to “Fix the Water.” Learning how nature gives us innumerable methods to clean, store, and/or direct our water (out of stormwater drains, for example) is exciting and can be easier and more effective than more standard solutions.

- The Ocean Research and Conservation Association (ORCA) employs biomimicry in its recommendation of “Buffered Shorelines”

- Measure and monitor fuller range of pollutants. Pollutants include agricultural, industrial, municipal, and residential wastes entering into our waters. Edie Widder at ORCA has developed the Kilroy system which monitors and maps water quality in real time. We need to know which pollutants are in our waters and where they are coming from (point source pollution). We must also be aware of new pollutants and toxic biological agents increasingly present in our waters: microplastics, forever chemicals like PFAS, and microcystin, a toxin generated by cyanobacteria (aka blue-green algae). One recent study by Dr. Widder found the herbicide, glyphosate, in 100% of the 125 local fish she examined.

- Green Infrastructure designs useful in our urban spaces, and in coastal resiliency during storms.

- Reduce, better yet, eliminate, the use of lawn chemicals. Widder states: Nothing but water should leave your yard or enter a storm drain.” All canals lead to the Lagoon and tributaries like the North Fork of the St. Lucie River.

- Take Plastics out of our waste stream.